+86-13732282311

merlin@xcellentcomposites.com

Let the world benefit from composite materials!

Research Progress of Aramid Flexible Stab-proof Materials

Mechanism of Stab Resistance in Flexible Anti-Stabbing Materials

Unlike rigid anti-stabbing materials, flexible anti-stabbing materials are typically composed of multiple layers of high-performance composites. During penetration by a blade, the composite fabric within the flexible material resists stabbing by utilizing friction, tensile deformation, and other mechanisms, ultimately dissipating the energy of the stabbing tool and securely locking its tip.

The stab resistance process involves the following stages:

- Initial Contact: When the blade first contacts the fabric, it exerts a force that interacts with the fabric's structure. Woven, knitted, or non-woven fabrics all exhibit a certain tightness, generating deformation to impede further penetration until the material reaches its deformation limit.

- Friction and Shear Forces: The blade's edge, having a certain width, creates tensile forces along the fabric's horizontal plane and shear forces in the vertical plane. The tensile forces cause fibers to shift, enlarging the slit, while shear forces lead to fiber breakage, further increasing the opening.

- Complete Penetration: Under the combined action of tensile and shear forces, the fabric is ultimately pierced.

To be effective, anti-stabbing materials must resist both tensile and shear forces, with shear resistance being the dominant factor.

Base Structures of Flexible Aramid Anti-Stabbing Materials

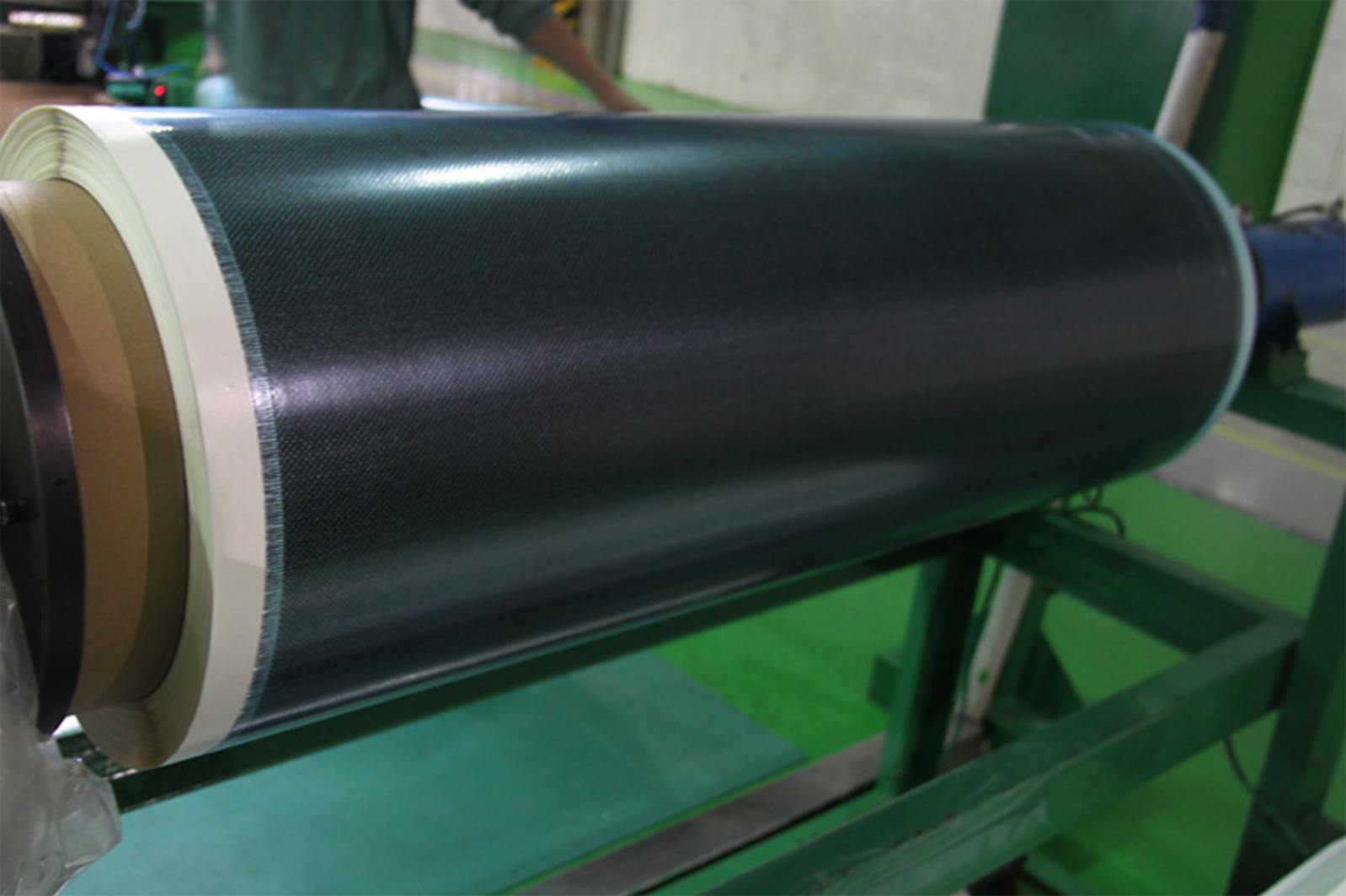

1.Aramid Unidirectional Fabric:

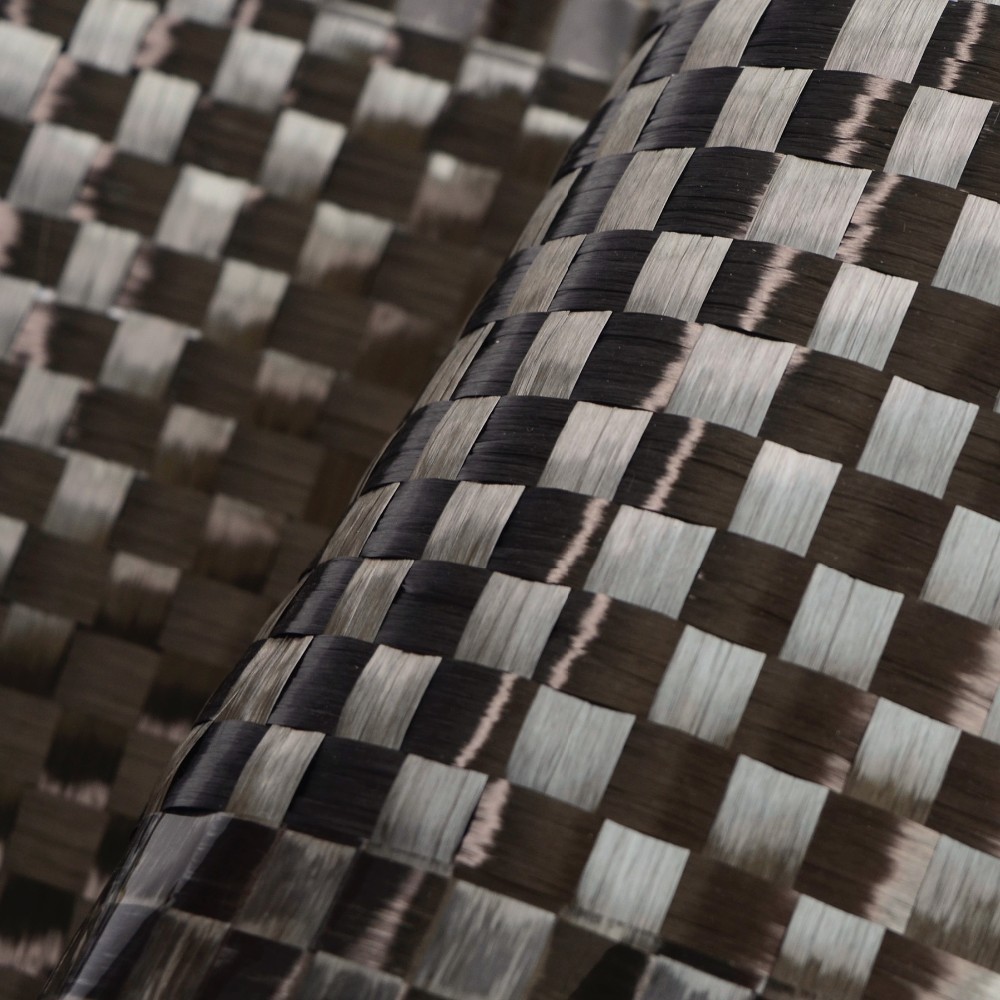

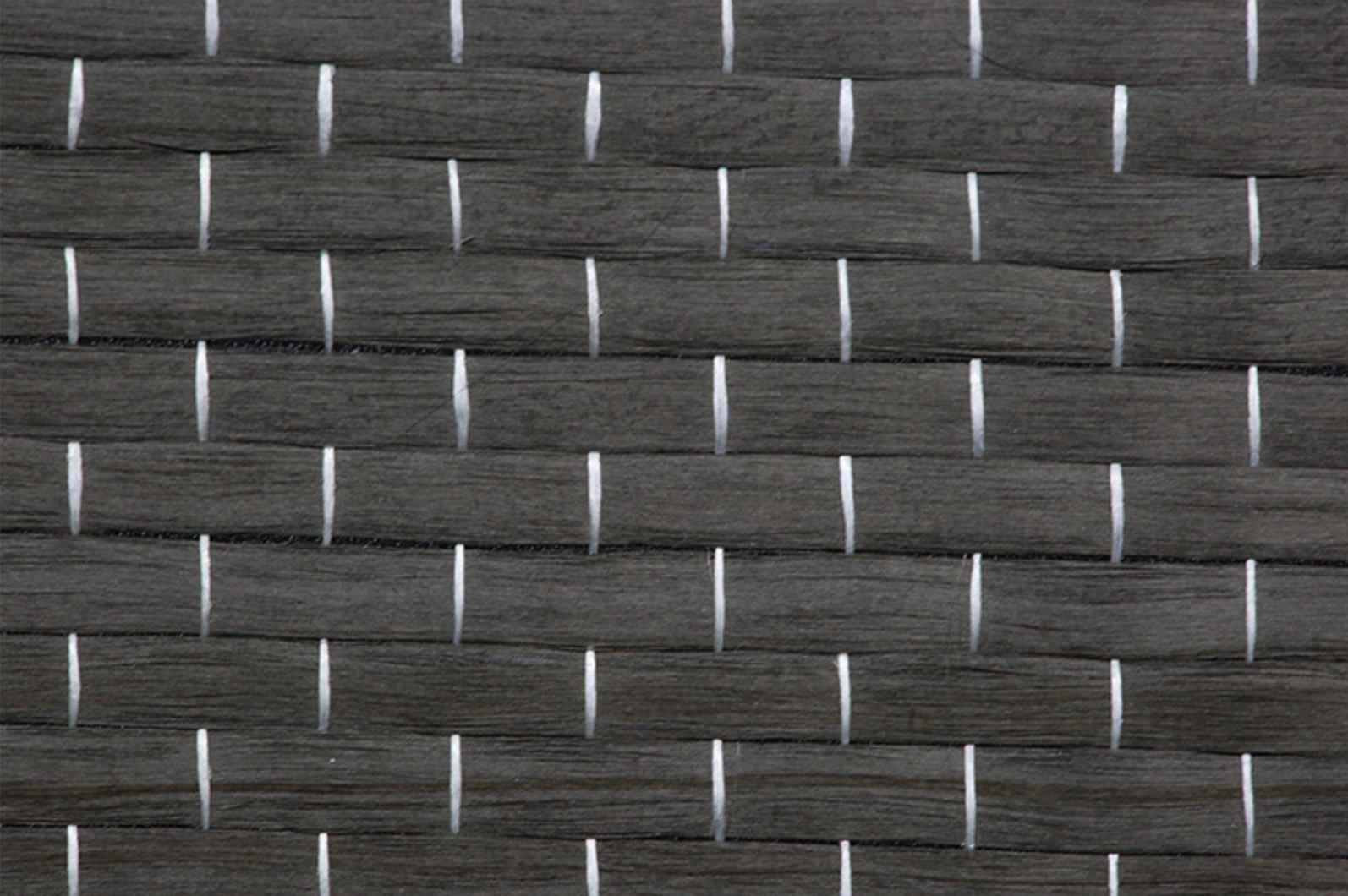

Unidirectional fabric is characterized by straight, untwisted fibers aligned in a single direction. It has no interlacing points on the surface, enabling stress waves to propagate without reflection, allowing for rapid energy absorption. Aramid unidirectional fabric is a flexible material commonly laminated orthogonally (0°/90°) with adhesives to enhance stab resistance. Adhesives serve to fix the fibers in place and reduce penetration depth.

For example, Wu Zhongwei et al. modified aramid unidirectional fabric with waterborne polyurethane resin to develop flexible anti-stabbing materials. They optimized the stab resistance by adjusting raw material quantities, pressure, and temperature, achieving a surface density of 7.65 kg/m², meeting the GA68-2008 stab resistance standards. However, due to the use of adhesive modifiers, the resulting material had poor flexibility, making it unsuitable for flexible anti-stabbing garments.

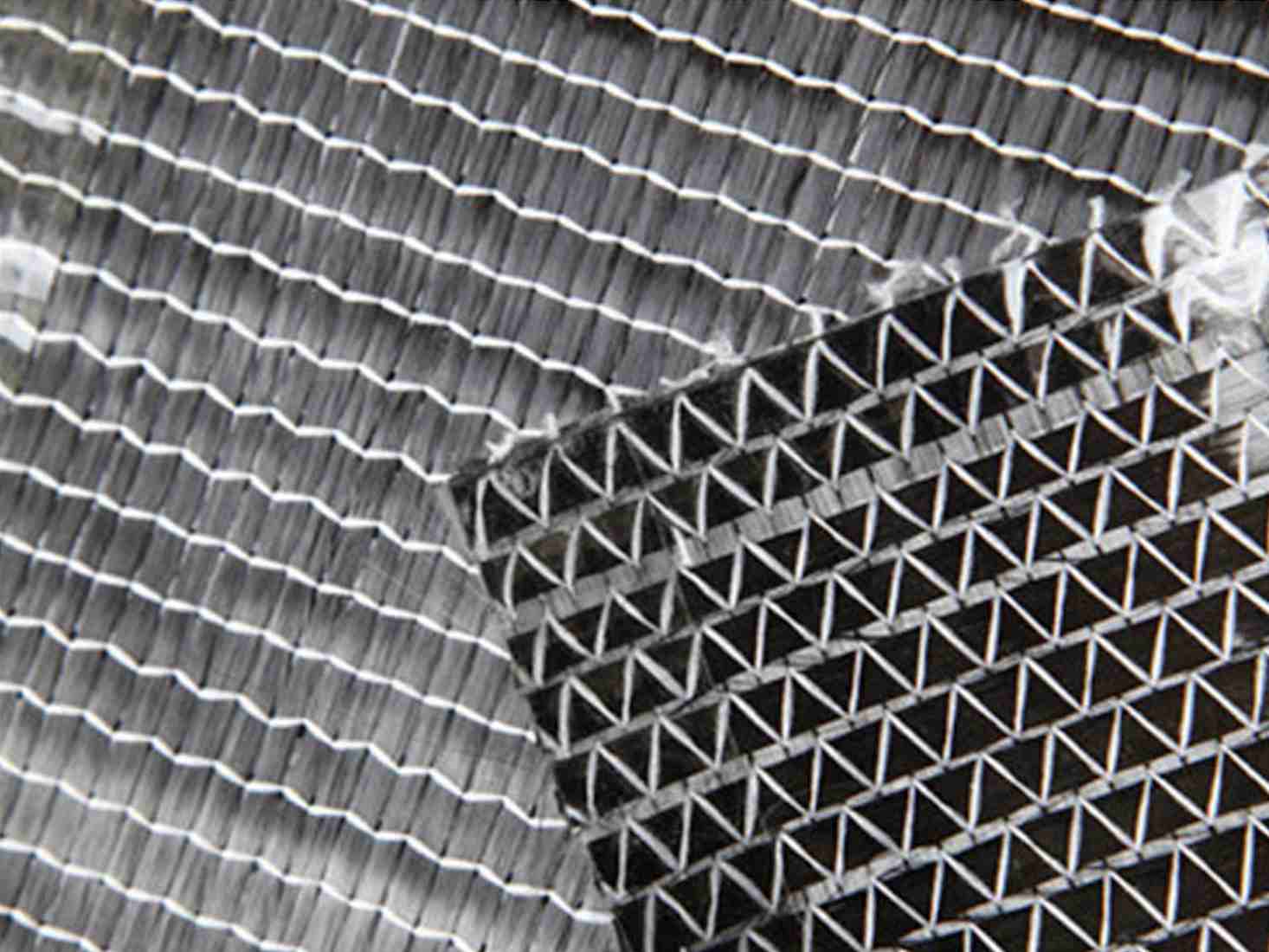

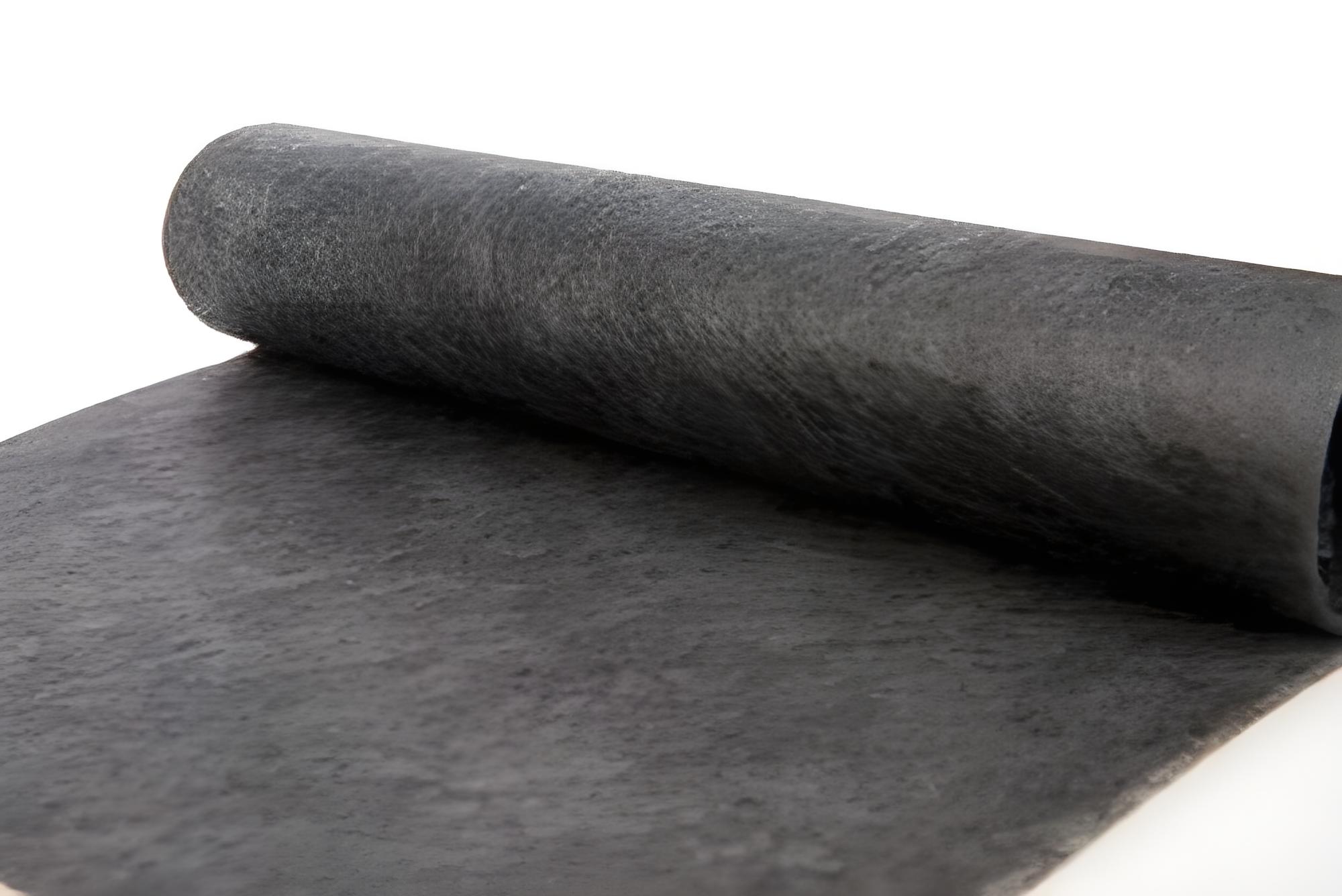

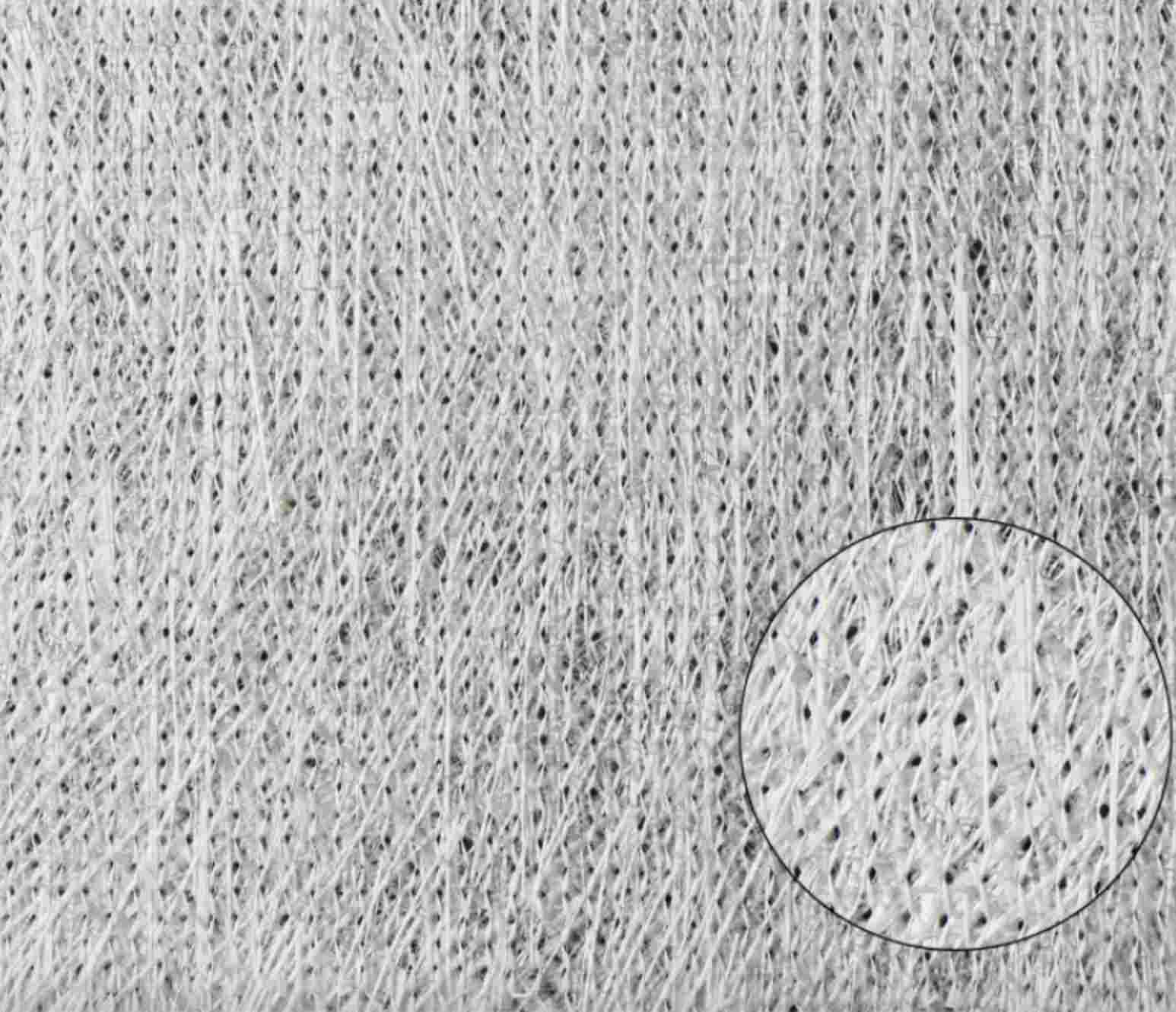

2.Aramid Non-Woven Fabric:

Unlike unidirectional fabrics, non-woven aramid fabrics feature randomly oriented fibers, providing isotropic properties and denser structures. These qualities offer better resistance against sharp objects. Non-woven fabrics are also simpler to produce, eco-friendly, and energy-efficient.

For instance, Li T-T and colleagues blended Kevlar fibers with polypropylene fibers in a 70:30 weight ratio, using needle punching and hot pressing to create Kevlar/PP composite non-woven fabrics. At a hot pressing temperature of 170°C, the material demonstrated excellent stab resistance. However, the loose internal fiber arrangement and weak bonding force of non-woven fabrics limit their overall cutting resistance when used independently.

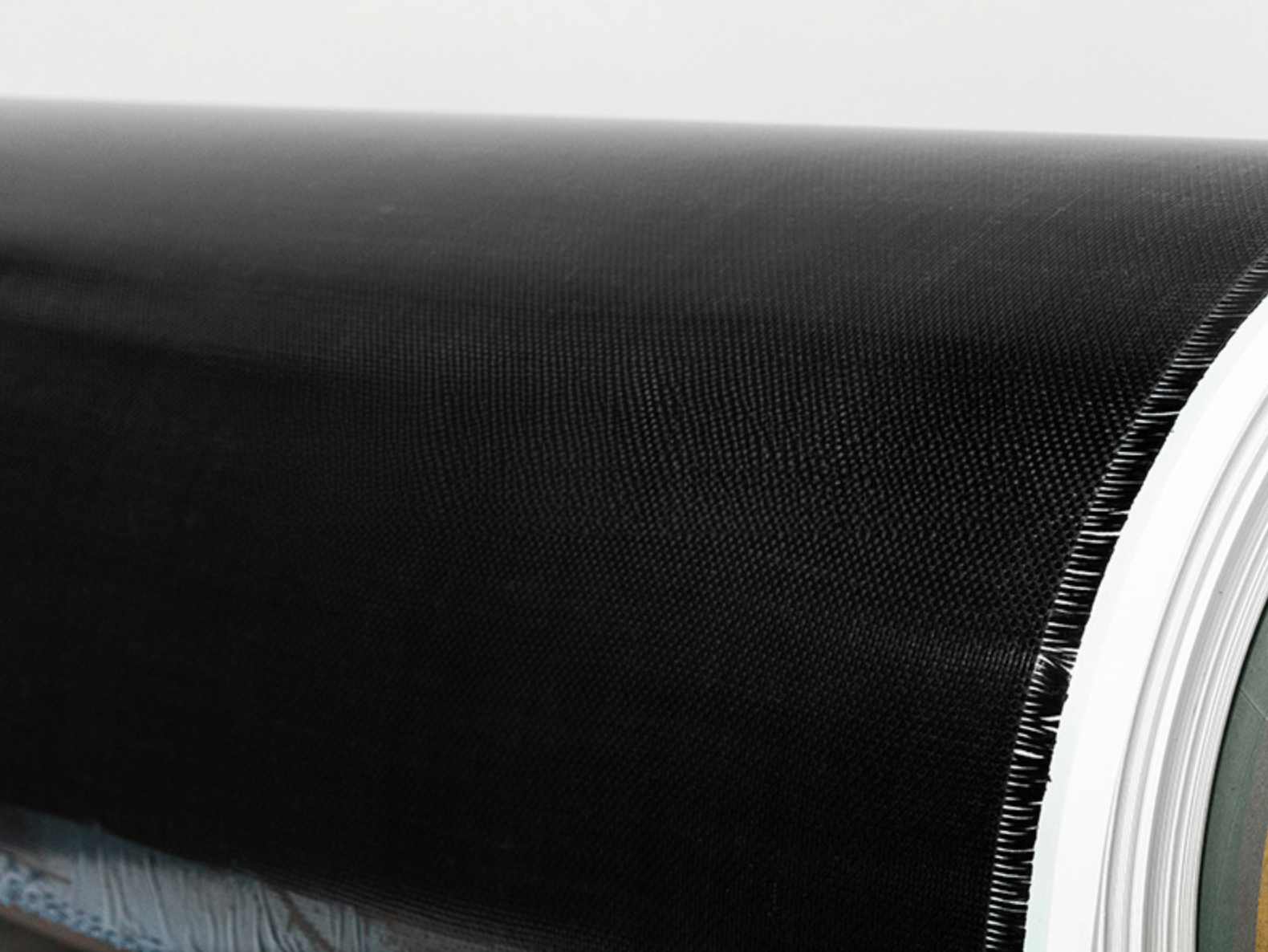

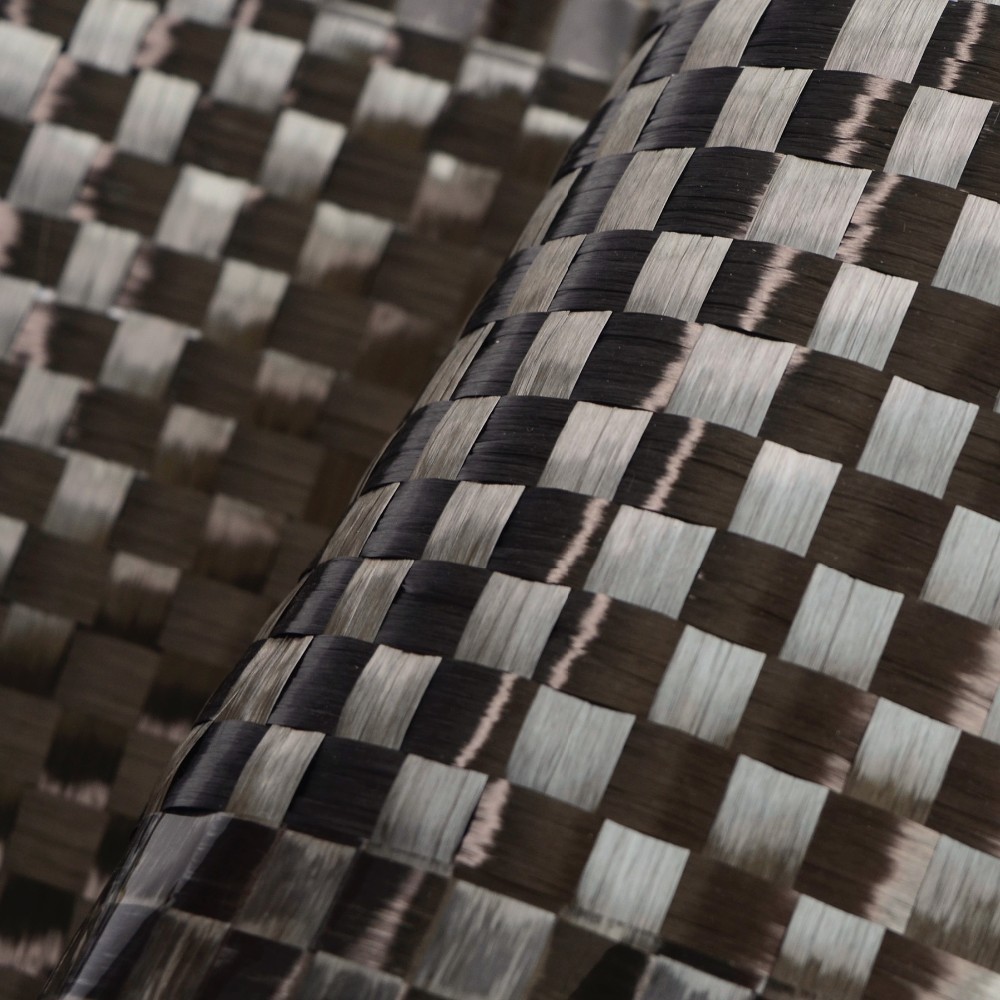

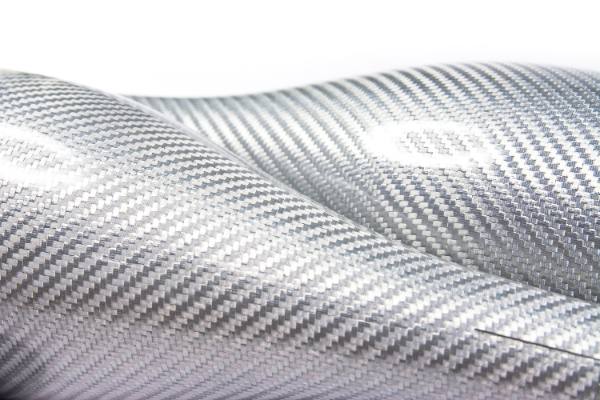

3.Aramid Woven Fabric:

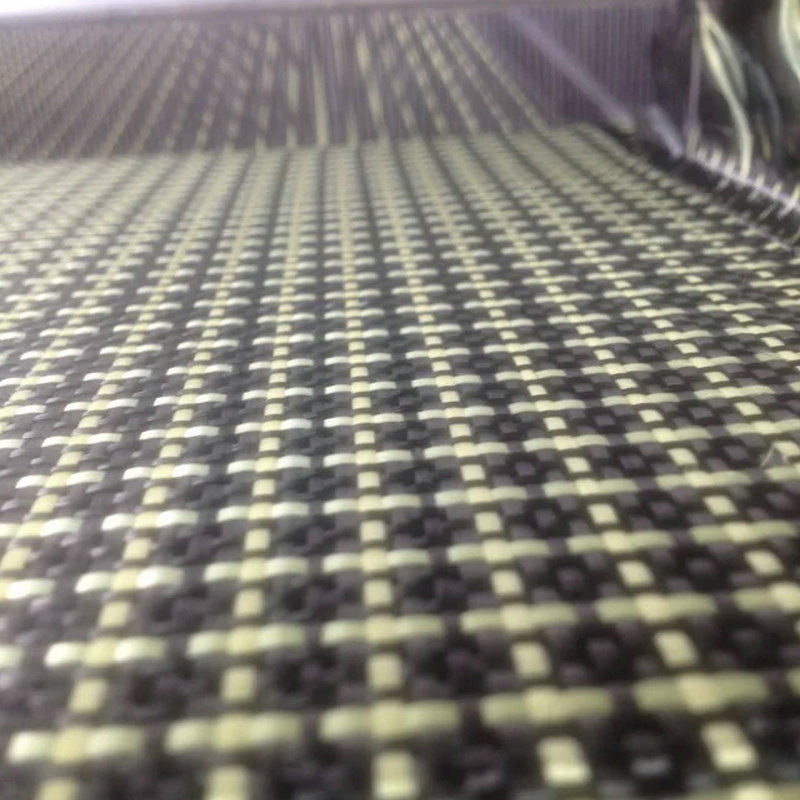

Aramid woven fabrics are formed by interlacing warp and weft yarns, creating a tight structure that effectively impedes penetration.

- Plain Weave: Features parallel yarns and tight structures, offering balanced strength.

- Twill Weave: Uses coarser yarns and looser structures, typically for heavy fabrics.

- Satin Weave: Has fewer interlacing points, making fibers prone to slippage under force.

While woven fabrics provide tight interlacing, once the blade cuts through the warp or weft yarns, the opening enlarges significantly, reducing stab resistance.

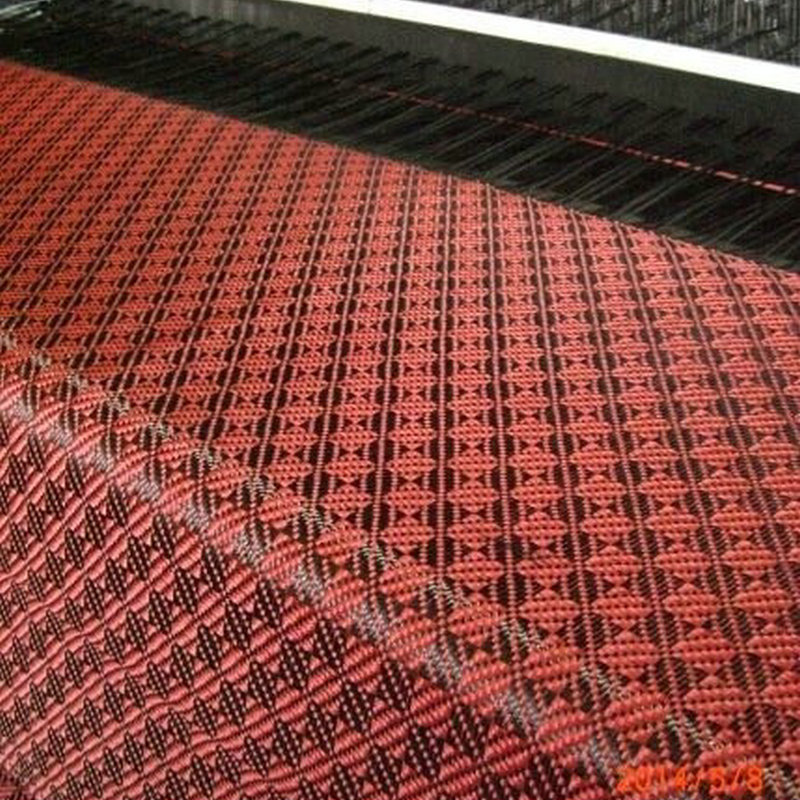

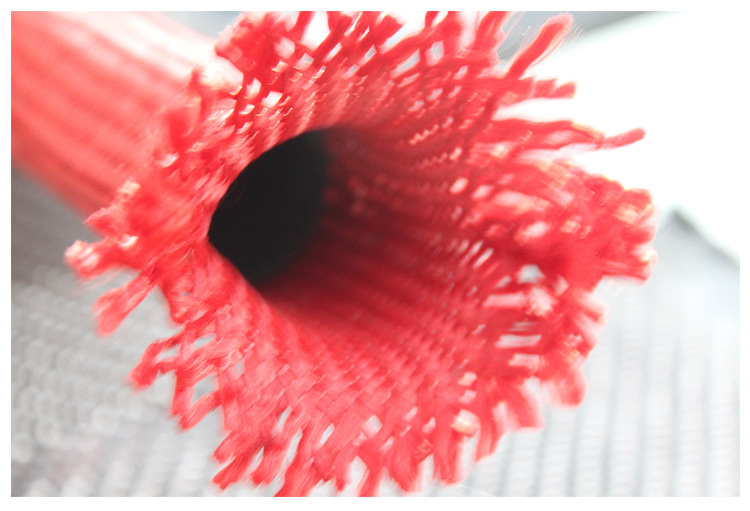

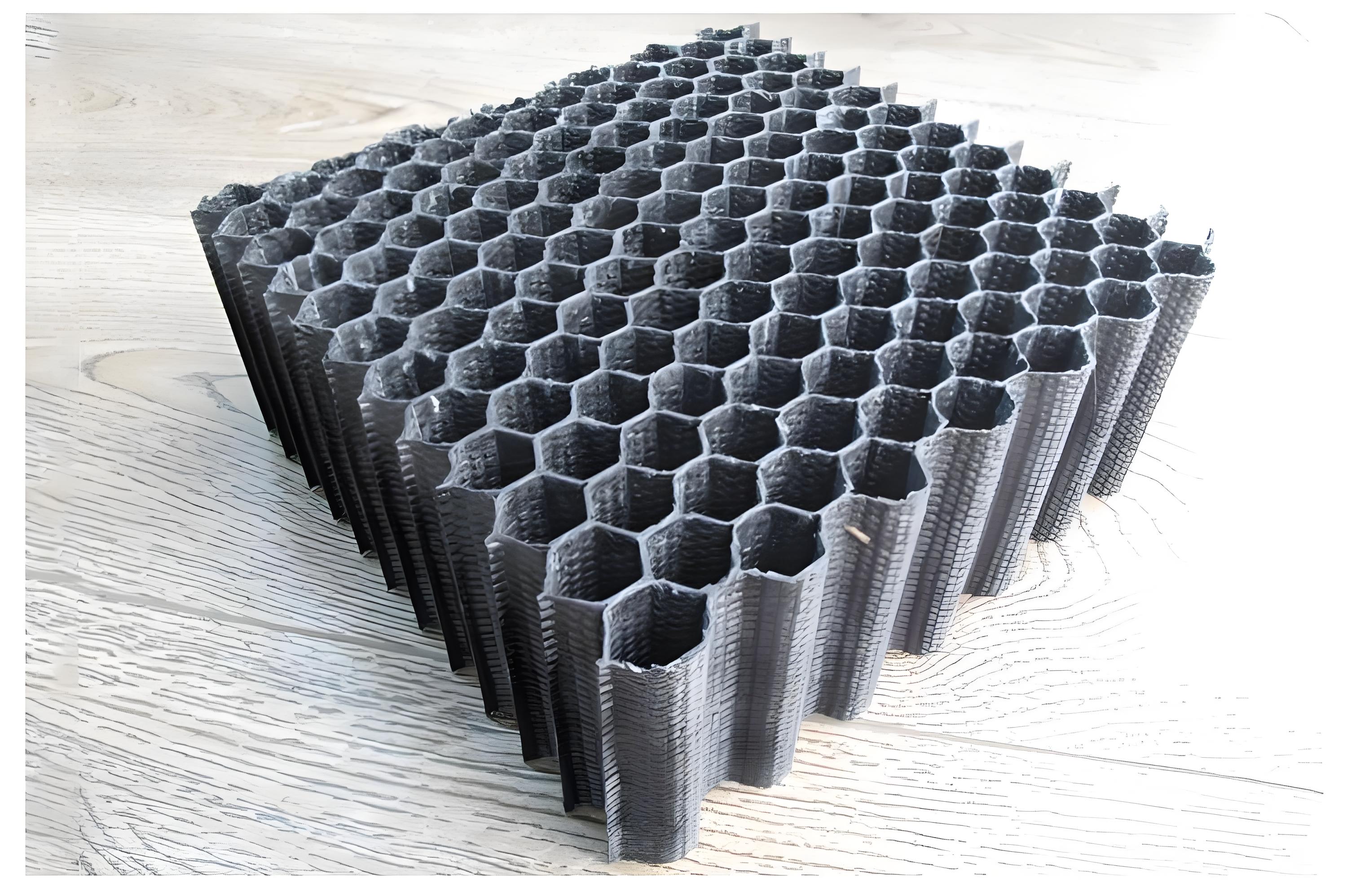

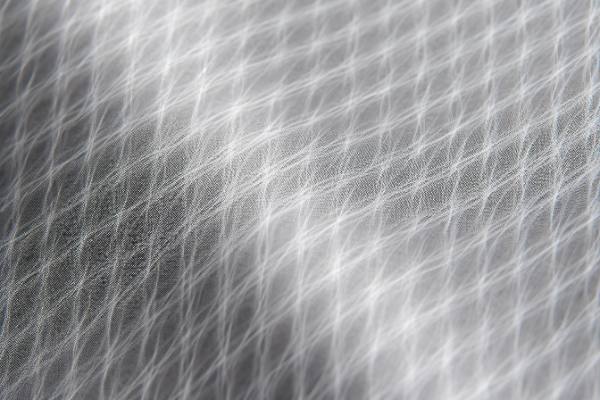

4.Aramid Knitted Fabric:

Aramid knitted fabrics consist of loops and wales. When a blade penetrates, the loops slide, tightening adjacent loops and increasing friction between fibers, thereby hindering further penetration. During this tightening process, some impact energy is absorbed. Once the loops are fully tensioned, the fabric achieves a "self-locking" state, preventing further penetration.

Li Ning and colleagues studied the "self-locking" phenomenon in knitted fabrics, finding that rib structures offered the best stab resistance, followed by plain weft knits and purl knits. The sequence of layered structures also influenced performance, with rib structures placed on the outermost layer achieving optimal results.

Modification of Aramid Flexible Anti-Stabbing Materials

3.1 Surface Coating Modification

Coating particles or thin films on the surface of aramid fibers enhances inter-fiber friction, improving their resistance to stabbing by dulling sharp metal blades through abrasion. For instance, Nayak R et al. applied boron carbide particles to modify aramid 1414 fabric surfaces, achieving a stabbing resistance force of 14 N at a penetration depth of 17 mm compared to only 4 N for uncoated fabric. The improved penetration resistance was attributed to the additional protective effect provided by the coating. Similarly, Javaid M U et al. studied the anti-stabbing mechanism of SiO₂-coated fabrics. Uncoated fabrics showed isolated interactions between yarns and the blade, leading to easy cutting. In contrast, SiO₂ coatings increased friction between yarns, reducing yarn displacement and enhancing resistance to stabbing.

Hard ceramic coatings combined with high-strength fabrics also prevent penetration from external impacts. For example, Gadow R et al. applied metal ceramic and oxide ceramic coatings to aramid fabrics using thermal spraying techniques. Static stabbing tests revealed significantly improved anti-stabbing performance for fabrics with hard ceramic coatings. Organic resins have also been employed for coating modifications. For instance, Zhuang Q et al. prepared aramid fabric/epoxy resin composites, reducing penetration depth from 37.3 mm to 4.8 mm, significantly enhancing anti-stabbing performance. The effect was further amplified with multi-layered composites.

Inorganic nanoparticles and organic resins are often synergistically combined to improve the anti-stabbing performance of aramid flexible materials. For example, Xia Minmin et al. discovered that boron carbide/epoxy resin-coated aramid 1414 fabrics increased tear strength from 50 N to approximately 300 N. Rubin W et al. coated aramid fibers with silicon carbide in a vinyl ester resin matrix, achieving optimal anti-stabbing performance at 20 wt% silicon carbide content. Similarly, Xiayun Z et al. developed flexible anti-stabbing materials by coating aramid fabrics with thermoplastic polyurethane/silica/shear-thickening fluid (STF). Fabrics coated with a solution containing 3% fumed silica demonstrated high resistance to knife and puncture forces.

3.2 Shear-Thickening Fluid (STF) Impregnation Modification

STF is a non-Newtonian fluid composed of dispersed phases and media. When aramid fibers modified with STF are subjected to external forces, the viscosity of the STF increases sharply, behaving like a solid and providing anti-stabbing protection. Once the force is removed, the viscosity returns to its initial liquid-like state, offering flexibility for protective materials. Li Danyang et al. prepared flexible anti-stabbing materials by impregnating aramid fabrics with STF. They found significant improvements in anti-stabbing performance across various fabric structures, with greater improvements observed with increased fabric interweaving points.

The type, particle size, content, and surface modification of nanoparticles in STF also influence fabric performance. For instance, Li et al. used SiO₂ particles with diameters of 12 nm and 75 nm as dispersed phases, along with multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) to prepare STF/MWCNT composites. Aramid fabrics impregnated with 12 nm SiO₂ particles exhibited superior knife resistance compared to those with 75 nm particles. Zhang Wangyang et al. found that pure aramid fabrics endured a load of 73 N at a stabbing depth of 30 mm, while STF-impregnated fabrics containing 30% SiO₂ and 70% PEG achieved the highest anti-stabbing strength under static conditions.

Despite the effectiveness of STF modifications, they may reduce breathability and moisture permeability, impacting comfort during wear.

3.3 Resin Composite Modification

Aramid-resin composite anti-stabbing materials combine the high strength and modulus of aramid fibers with the multifunctional characteristics of resin matrices. Mayo J B et al. found that thermoplastic resins (polyethylene, polymethyl methacrylate, and polyethylene-methyl methacrylate copolymers) significantly improved the anti-stabbing performance of JSP 706 Kevlar fibers. By adjusting resin types and thicknesses, fabrics with varying anti-stabbing properties were obtained.

Liu Yulong combined SiO₂ nanoparticles with Surlyn resin for composite modification of aramid fibers. At a resin content of 33 wt%, 36 layers were needed to withstand 24 J of energy, whereas only 30 layers were required at a resin content of 44 wt%. Kim H et al. observed that low-density polyethylene (LDPE) enhanced the anti-penetration process of Kevlar fabrics more effectively than epoxy resin, though LDPE's performance was limited to the initial stages of penetration.

The stacking method of resin and aramid fabrics also influences performance. For example, Chen Li and Wang Botao applied polyurethane to aramid plain weave fabrics using wet coating, transfer coating, and dry direct coating methods. Among these, the transfer coating method provided the best anti-stabbing performance.

3.4 Fiber Composite Modification

Blending aramid fibers with other fibers using core-spun yarn techniques is another method for producing high-performance flexible anti-stabbing materials. For instance, Tien D T et al. studied woven fabrics made from aramid-cotton core-spun yarns with different surface densities. When the weight ratio of aramid to cotton was 1:2.5, and the warp and weft densities were 16.4 threads/cm and 8.4 threads/cm, respectively, the materials demonstrated excellent wearability and improved anti-stabbing performance.

The number and arrangement of fiber layers also affect performance. Du Lingling et al. investigated the influence of stacking layers on the anti-stabbing properties of fabrics made from aramid staple yarns and stainless steel filaments. They found that increasing the number of layers improved knife resistance.

Conclusion

Currently, woven, knitted, nonwoven, and unidirectional fabrics made from aramid fibers are used for producing flexible anti-stabbing materials. Modification methods such as resin composites, surface coatings, and STF impregnation enhance the performance of high-performance textile products, driving advancements in aramid flexible anti-stabbing materials. However, high costs and reduced comfort due to certain finishing methods remain challenges.

Read More: Research Status and Prospect of Anti-Cutting Fabric Such As UHMWPE Fiber

Popular Composite Materials

Popular Composite Materials

Composites Knowledge Hub

Composites Knowledge Hub